The Power of Critical Sensemaking in Shaping Future(s)

The Power of Critical Sensemaking in Shaping Future(s)

As 2024 draws to a close, we’re foraging for the right note to end things on. What feels like an apt response to such a tumultuous year? What are the lessons we’ve learned, and how can we begin to enact them? These are difficult questions to unknot, but one thread that seems to have rippled through the fabric of the year is the importance of critical thinking, especially in relation to planning ahead for 2025.

In recent conversations about the future of retail (and countless other industries), we’ve noticed a pattern quite familiar in foresight work. While we’ve seen some fascinating explorations, the broader trends, signals, and ideas that emerge often feel … flat. Predictable. Despite all the prompt engineering, it’s always the same conversation: immersive digital experience meets physical space, with maybe a dash of AI-driven convenience.

But where is the surprise? Where is the friction that sparks cultural imagination, invention, and innovation? What about the tiny edge cases and the unexpected whispers?

It’s tempting to want to gather, smooth, and reflect what’s already being said, and while this can be useful and generative in its own way, at times we might find ourselves stuck in a loop, recycling familiar patterns instead of breaking new ground.

This made us reflect on something essential to all futures work: the power of critical sensemaking.

What is sensemaking?

For Karl Weick, the prominent organisational theorist and emeritus professor at the University of Michigan who coined the term, sensemaking is a creative and interpretive process of assigning significance to unforeseen circumstances. It’s a retrospective practice of making something “sensible” in ways that aren’t purely cognitive. ‘The more ready you are to deal with reality,’ he’s noted, ‘the more you can acknowledge its complexity.’

Sensemaking is a form of meaning-making in ambiguous situations—both the large-scale uncertainties and the everyday precarities. It’s an ‘unending dialogue between partly opaque action outcomes and deliberate probing’; a tool for understanding how different meanings, triggered by uncertainty, are formed from the same event.

Sensemaking speaks to our capacity to navigate interruptions, to reorganise after a break in routine. Weick observes that disruptions, both mundane and catastrophic, ask individuals to make sense of both ‘what is occurring now, and to consider what should be done next’. From this lens, sensemaking is always comparative: a process of driving present actions based on information gleaned from past unfoldings.

What makes sensemaking critical?

Critical sensemaking is not just about identifying trends or following the mainstream narrative; it’s about navigating complexity, exploring the grey areas, and drawing connections between seemingly unconnected ideas. It’s about spotting weak signals and engaging with the friction that exists on the edges—because that’s where the real possibility for change lies.

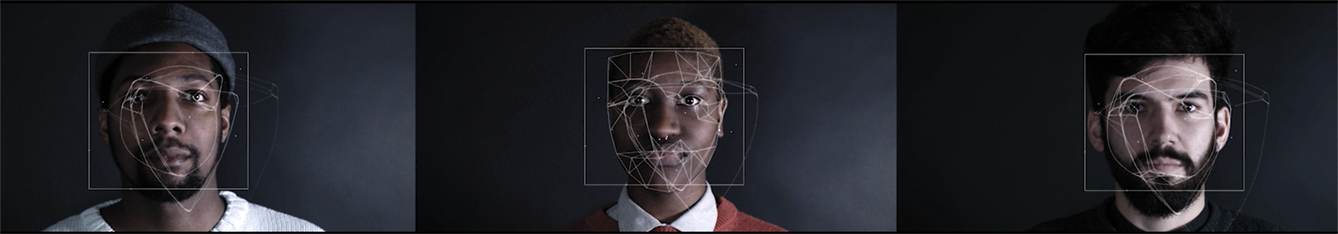

Critical sensemaking serving as a useful lens to interrogate how individual actions interact with broader social issues. It’s about moving from the question “what” to “why”. Critical sensemaking isn’t just a skill; it’s a way of engaging with the world that allows us to imagine futures that are rich, complex, and full of potential.

Reports about the future can tend toward the prescriptive, but if we’ve learned anything from our fifteen years in the field, it’s that trends aren’t always the best indicators for how events will unfold. Futures evolve by way of unexpected twists and turns, and a valuable tool to navigate through the thicket is our capacity for critical understanding, as well as our imagination.

Critical sensemaking in practice

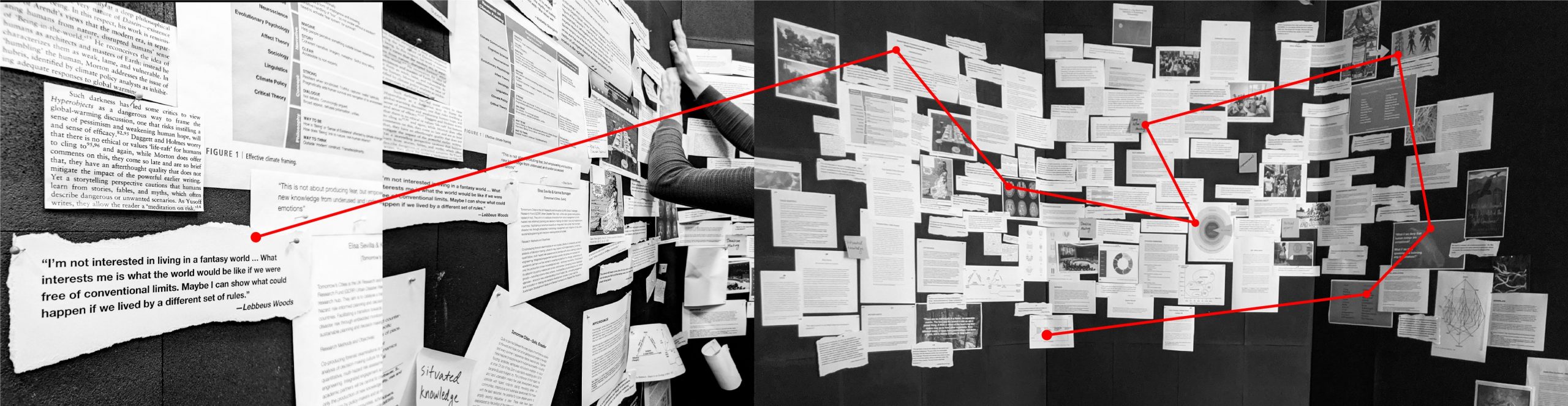

At Superflux, this is what excites us. We don’t just look for the key trends or the obvious outliers. We embrace the messiness, the uncertainty, and the ambiguity, because we know that’s where new futures begin to take shape.

Joan Didion famously wrote that ‘we tell ourselves stories in order to live.’ What’s less often quoted is the second half of what she penned: ‘We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers’—or futurists, thinkers, human beings—‘by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.’

When we embrace critical sensemaking, we’re contending with the discomfort of knowing that the stories we tell ourselves aren’t always linear. We’re pushing ourselves beyond the familiar, inviting exploration at the edges of possibility. It’s not always easy. This work requires us to hold multiple, often contradictory ideas in tension. It invites us to question our own assumptions and biases. But this is where true innovation thrives.

Critical sensemaking isn’t about having all the answers, but about asking better questions. It’s about developing the mental agility to connect dots that aren’t obviously related. It’s about sitting with uncertainty and allowing it to reveal new pathways forward. It’s a cartography of the future, a way of mapping what we don’t entirely know and can’t always prepare for.

Going behind the blueprints

In his seminal paper on sensemaking and enactment, Weick considers the blind spots that emerge under conditions of secrecy in chemical plants:

‘When people make a public commitment that an operating gauge is inoperative, the last thing they will consider during a crisis is that the gauge is operating. Had they not made the commitment, the blind spot would not be so persistent.’

– Karl Weick, ‘Enacted Sensemaking in Crisis Situations’, Journal of Management Studies 25.4 (July 1988)

What happens when we go behind the blueprints, when we start to question and critique the things we’ve been conditioned to accept as immovable truths?

We need to adopt a collective stance of epistemic humility if we’re going to meet the demands of both our turbulent present and emergent futures. We need to develop a healthy distaste for absolutism and a zest for alternative viewpoints that may or may not contradict what we hold to be true, to lean into the tacit understanding that the only certainty is that nothing can be known—or predicted—for certain, and to accept that reality is often stranger than fiction.

Critical sensemaking asks us to slacken our hold on the myth of unchangeability, to question even the things that seem to underpin our entire way of experiencing the world, and to comprehend just how permeable the boundaries are between stability and fluctuation.

With 2025 on the horizon, we invite our readers to tread lightly with the prediction decks that are bound to be hitting your inboxes soon. Attempting to shape our collective futures is to grapple with the fact that futures are elastic, sticky, and indeterminate. Being able to make sense of seemingly chaotic information, to spot patterns and opportunities where others see only the daily clamour, can set us apart.

Superflux Featured on BBC Radio 4

Superflux Featured on BBC Radio 4  ‘Our Friends Electric’ acquired by the European Patent Office

‘Our Friends Electric’ acquired by the European Patent Office  Stop Shouting Future, Start Doing It

Stop Shouting Future, Start Doing It

TED Talk: Why We Need To Imagine Different Futures

TED Talk: Why We Need To Imagine Different Futures  Cartographies of Imagination

Cartographies of Imagination  Tackling the Ethical Challenges of Slippery Technology

Tackling the Ethical Challenges of Slippery Technology  Future(s) of Power Launch Event

Future(s) of Power Launch Event  CAN SPECULATIVE EVIDENCE INFORM DECISION MAKING?

CAN SPECULATIVE EVIDENCE INFORM DECISION MAKING?