Projects

Better Care

Tech fixes are typically implemented from the top down, promising a seamless experience in which gadgets blend into the background, effortlessly improving lives. The reality is, however, that such solutions are often designed for fictional characters – theoretical end users whose daily realities aren’t taken into account. In real life, new technologies never function as promised: there are always glitches and unintended consequences. So what would a future look like in which we apply technology to support the UK’s ailing social care system?

THE FILM

2025: A Better Care Future

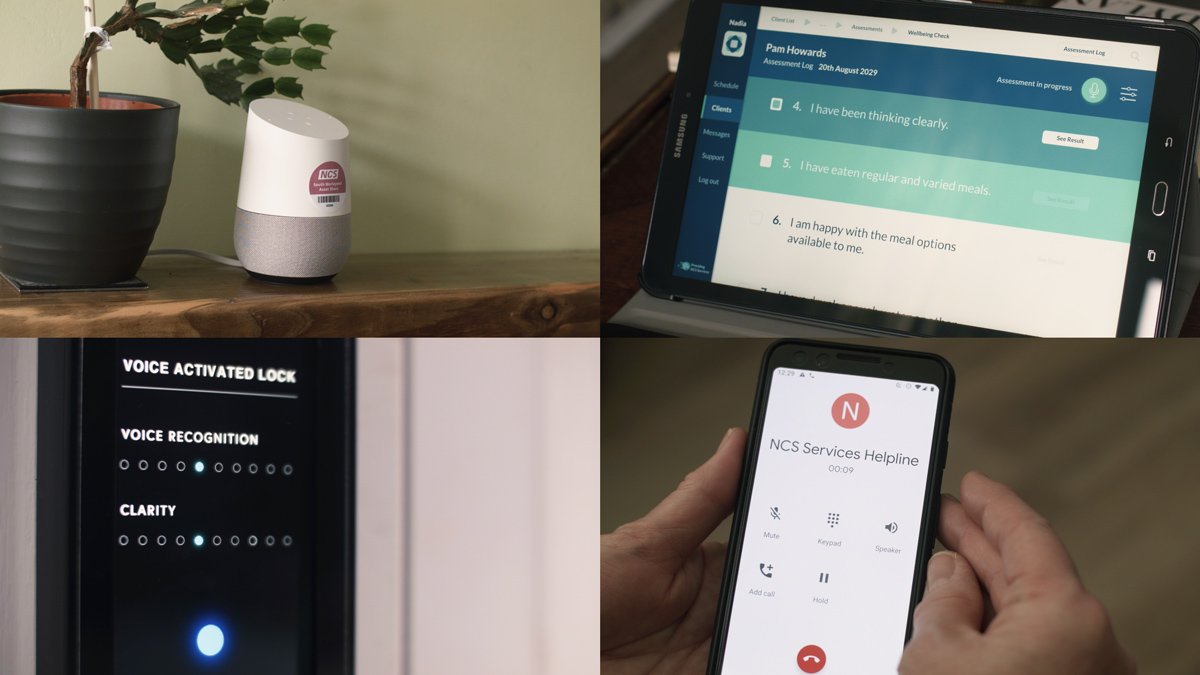

It’s 2025, and Nadia, a care worker for the now year-old National Care Service (NCS), is on her way in a driverless car to visit Pam, an elderly woman whose stroke has left her mobility impaired. Nadia’s visit is routine, and with the help of gadgets like a robotic walking stick and a machine that reminds her to take her meds, Pam has everything she needs in the way of basic support.

One thing’s driving her crazy, though. Her voice-activated lock, aka VAL, won’t work reliably, and she has to keep getting up to answer the door. Nadia’s visits become a series of increasingly frustrating troubleshooting sessions to fix VAL – culminating in an absurdly complicated hacked-together device to trick it into working. Unintended consequences aside, the creation of the NCS does seem a positive move overall. Radio chatter in the background and Pam’s newspaper headlines indicate that, while controversial, government investment in social care has so far proven economically and socially successful.

Far from portraying a glossy utopia where machines seamlessly assume responsibility for gaps in social care, our film ‘2025: A Better Care Future’ portrays a more realistic – maybe even mundane – ‘frictionful’ near future in which technology itself doesn’t quite work and needs human support. The new government-funded national care system is supposed to help everyone, but it’s also broken in parts – not just on a technological but also a bureaucratic level. Given the opportunity, though, people band together to overcome tech issues, finding human solutions in the face of these failings.

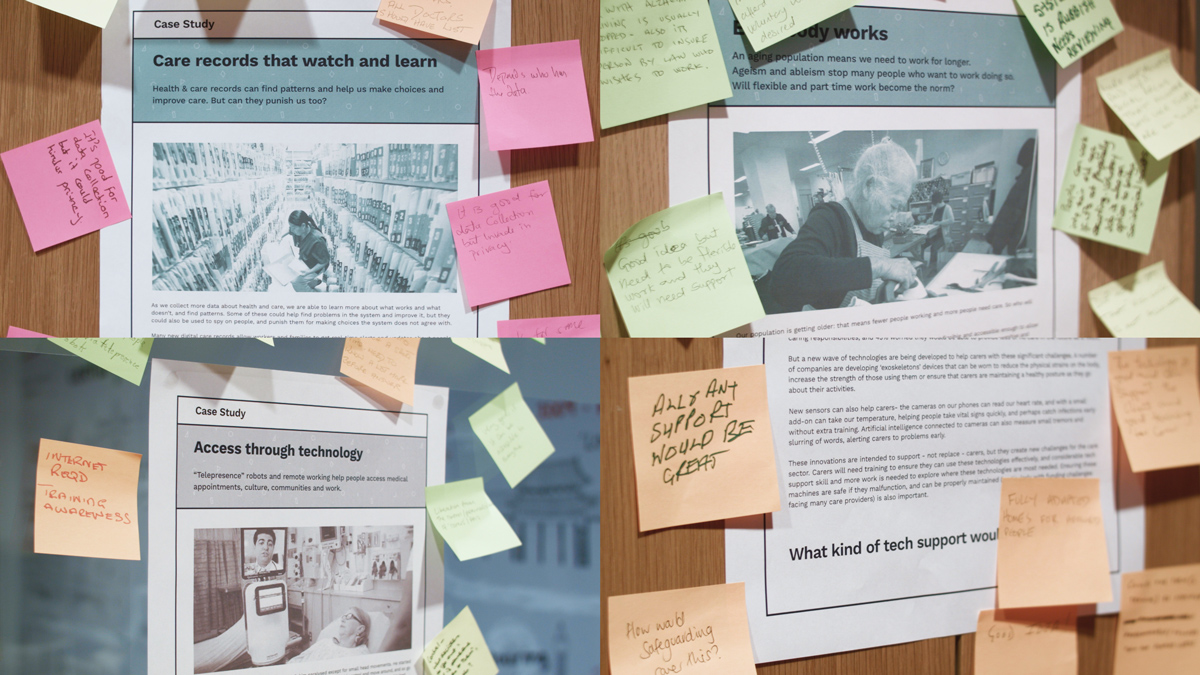

As part of the process of creating the film, we attended workshops led by commissioning client Doteveryone to learn about the experience of real-life people who currently require care, and who’d therefore be the beneficiaries of our proposed system. The film intends to give voice to these end users; featuring actors with personal experience of receiving social care services, providing unpaid care or working in the care sector.

Our key propositions for a future of care:

- National Care Service (NCS): The government has rolled out a social care analog to the NHS. The existence of an NCS is predicated on an active stance that every member of society is equally valued, regardless of gender, race or social status.

- Royal College of Carers: This officially recognized academic body acknowledges that caring is a profession and requires not only appropriate training, education and accreditation but ensures that carers are paid properly. This also assumes a better social status for care workers, who are currently undervalued and overworked.

- Centaur care: Care will be a joint effort between human and machine; neither one nor the other will dominate. Applications of technology need to be carefully considered because human well-being can’t be translated into a set of metrics for optimisation.

- Policy changes: Laws mandating government investment in nationalised care is the basis for education and services funding, ensuring proper wages for carers. This also means that carers are given the same employment rights as other labourers. Improvement in employment conditions translate into improved carer well-being and, in turn, higher-quality time and attention they can provide care receivers.

- Hacks and workarounds: The film’s portrayal of the characters hacking together a whole box of devices in order to make VAL work – along with several other smaller hacks and workarounds – is a way for them to come together to hack bureaucracy.

- Community care assets: The devices portrayed in the film – VAL, Pam’s robotic cane, the telepresence robot – are seen as community assets shared by the NCS on a need basis.

THE TAKEAWAY

Technologies may solve problems, but the need for human connection is an eternal and essential requirement that can never be replaced. Whatever technology-based systems we build to help us care for each other must incorporate this idea at their core.

PROJECT BACKGROUND

The current state of care in the UK is in crisis. Care worker pay is often less than the living wage, workers don’t receive proper training and lack of government funding is taxing the already overstretched sector. Projecting forward, by 2028 England’s social care sector will be short more than 400,000 workers.

To address the problem, responsible-tech think tank Doteveryone invited Superflux to help them ‘optimistically reimagine care systems within changing technological, social, political and economic contexts’.

They posed the question: ‘How can data and technologies support a sustainable, effective, fair care system?’ While new technologies are often touted as an obvious stopgap, what, in reality, will the relationship between humans and machines in the context of care look like? Will it make life easier or more complicated for both care workers and patients? How would such a system affect the economy? And what policies need to be in place to create such a system?

RESEARCH AND DESIGN APPROACH

We began by doing extensive research into how we reached the present crisis in care, possible new social and economic models in which the care sector is recognised as equal to other labour, the role of older people not just as recipients of care but as volunteer caregivers themselves, existing technologies used for caregiving, legal frameworks and more.

We also participated in workshops led by Doteveryone with present-day care receivers, and conducted interviews with a variety of experts. One conversation in particular, with IPPR senior economist Carys Roberts, informed the making of our film. Roberts shared her thoughts about the economics of care, and on how government budget reallocation might be able to address many of the challenges currently being faced.

Our research showed that nationalised care will result in economic benefit. A case in point: maternity care. Roberts cited evidence during our interview that investment in maternity care results in economically positive outcomes. We also learned that while machines will help bridge the care gap, they are not likely to take over. All our care needs will not just be automated; human care is important, too.

Following our research, we led our speculative design phase by imagining a range of scenarios and ideas – from a public communications campaign to a political intervention on mainstream media. Ultimately we settled on making this short film that depicts a future – or even a plausible present – in which humans and machines work together in a centaur-like, albeit glitchy, relationship. Humans are still required not only to perform caretaking tasks, but to troubleshoot imperfect technology.

Meanwhile, playing out quietly in the background are the positive policy changes, design updates, economic and political shifts that have made this human-machine dynamic possible. These shifts go almost unnoticed by the characters in the film. What ultimately stands out is the nature of the bonds between caregiver, care receiver and machines.

Further reading:

‘Caring Labor’ by Nancy Folbre

The Buurtzorg Model – Case Study by The Commonwealth Fund

Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work – International Labour Organisation Report

‘Finally, a breakthrough alternative to growth economics – the doughnut’ by George Monbiot

DWP spends £39m defending decisions to strip benefits from sick and disabled people

It’s time for a new social contract between the generations

The Guardian view on a caring capitalism: healing an unhappy society

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs vs. The Max Neef Model of Human Scale development