Blog

Cartographies of Imagination

Cartographies of Imagination is an essay about our project MAPLAB, where we develop cartographic imaginaries of Eindhoven with children. The project’s ambition is to show city planners, decision-makers and technologists, how our cities could be different if we consider children as key fellow citizens, rather then future citizens.

The project was commissioned by the DATAstudio, Mayor’s Office at the City of Eindhoven and Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam. For this project, we collaborated with Beam it Up, and Sophie Rijswijk with schoolchildren in Eindhoven. This essay is originally published in ‘Becoming a Smart Society’ (Het Nieuwe Instuut, 2018) available in Dutch and English.

INTRODUCTION

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” [1] Jane Jacobs, US-Canadian journalist, author, and activist.

Eindhoven has been called the “Philips City” ever since Philips decided to set up its headquarters there in 1914. More recently, the city has experienced a resurrection after a major downturn in the 1980s and 1990s, spurred by the residence of several technology companies. So when the drive to create “smart cities” spread across many parts of the world, it seemed like an obvious fit for Eindhoven. With its “living labs”, start-up companies, thriving technology university, and infrastructure primarily created by Philips, Eindhoven was on its way to embrace the ‘smart-city’ philosophy fairly smoothly.

However, about three years ago, Eindhoven’s Mayor and City Council began to raise critical questions about what it means for a city to be “smart”. The city council’s policy framework published on 23 April 2015 speaks of a paradigm shift in its role – from deciding to facilitating, from control to trust, and from competition to cooperation. Meanwhile, at the invitation of alderwoman MaryAnn Schreurs, Het Nieuwe Instituut curated a critical cultural programme centred on the ideas of the participatory society and the smart city. Though two separate trajectories, the Council and the Institute began to articulate a vision of the city that would be “participatory”, implying the need for it to generate a constant and sustained dialogue with its citizens. I was invited by Het Nieuwe Instituut to be part of an advisory group to help steer and kick-start activities in this direction.

As the DATAstudio began to develop activities to realise this ambition, I was keen to draw attention to a group of citizens who are often not considered as participants and decision makers in our cities: children. Most of the time, children are not considered citizens but rather future citizens. Of a population of 226,921 people in Eindhoven, 15 per cent are children under 14 years. In what ways could the DATAstudio encourage children to take part in shaping their neighbourhoods? How can we shift the focus from the idea of a child coming into the world to a child being in the world?

CONTEXT

Alfred Korzybski’s oft-quoted maxim “A map is not the territory” [3] remains one of the most important statements about the difference between perceptions of reality and reality itself – and particularly for those working on maps. Korzybski went on to argue that “an ideal map would contain the map of the map, the map of the map of the map, etc., endlessly”; Korzybski and some of his contemporaries termed this idea “characteristic self-reflexiveness”. Scholars over the years have inferred that, whilst mapping is a method of gathering, ordering and recording knowledge, all maps are to some extent products of the imagination. No map is ever truly the objective description of a place that it purports to be. Every map is shaped and coloured by political, cultural and social conditions, and by the personal experiences and imaginative projections of its maker. Maps can be enhanced by imaginative embellishments; they can show imaginary places and present collective aspirations and hopes for the future.

However, today, with the rise of big data, we see a renewed attempt to conflate the map and the territory. Endlessly aggregating flows of people and their locations, things and activities are continuously mapped into ever-larger undifferentiated masses. As Lindsay Caplan writes in her e-flux editorial, “Big data oscillates in the space between a map and a territory. It is a seductive mode of representation and is therefore often confused to be both. It is important to recognise this confusion because data representations are critical. What data means – how it is interpreted, and to what ends – has implications not only for privacy and security but also for how we exist and understand our position as humans in the world.”[4]

This is now becoming more important than ever before. The constant stockpiling of data collected on everything from our most intimate activities to the flows of human and non-human currents across our cities is intrinsically linked to the idea of the “smart city”, where every activity, movement, interaction and relationship becomes an abstracted, measurable, quantifiable asset, flattened onto a two-dimensional map. This ideology becomes the foundation on which the smart city (or a future smart city) and its use are configured and regulated. Whilst they are invariably “smart” in their ability to use data sets and maps as “evidence” or facts about the status quo and then build upon these assumptions, ultimately this is problematic. These are not simple facts but rather facts represented through a specific technology that does not allow for “thick data”[5] – the stories and social imaginaries of the people who collectively make cities what they are.

This seductive contemporary vision of the city is not entirely different from historical ones. Though the contemporary genre of urban techno-fantasy seen in visions of the smart city is new, city planners (and city officials) have often approached cities from a top-down perspective, resulting in the social wars over urban justice fought by people like Jane Jacobs, Jan Gehl, Ellen Dunham-Jones and so many others. Besides being designed and built in ways that were top-down and ignorant of life on the ground, our cities have also been created for specific segments of adults. Children very rarely play a role in the design of future cities, yet they access and continuously use the shared resources of cities, such as streets, parks, town centres, playgrounds and transport systems. Whenever Michael takes his inflatable boat out onto the lake, Old Man Richardson gets out his BB gun – or so Michael claims. The 12-year old artist has made a fantasy map of a paintball payback.

Michael Jensen, Untitled (Revenge Map), 2003. Whenever Michael takes his inflatable boat out onto the lake, Old Man Richardson gets out his BB gun – or so Michael claims. The 12-year-old artist has made a fantasy map of a paintball payback.

How can urbanists, city planners, technologists and all those in local government responsible for creating and building cities be inspired to develop inclusive, liveable smart cities that respond to and accommodate children? Designing, planning and building genuinely inclusive cities require vision, foresight, knowledge, cultural sensitivity and a desire to create long-term legacies. Showing the world through the eyes of a young child can create powerful leverage with city planners and decision-makers formulating future visions of cities. Bringing this perspective to urban planning through mapping, drawing and storytelling with children is not new. Let me describe a few inspiring examples.

A Canadian cognitive-mapping project, KIDSMAP6, asked children in British Columbia to draw mental maps of their neighbourhoods. Whilst the study recognises the inherent limitations of cognitive-map work with children, the value here lies in the act of physically locating and representing places of importance – vocalising the interests and values of invisible and overlooked constituents.

Across India, an initiative facilitated through local “child clubs” in slums from Mumbai to New Delhi and Hyderabad and championed by the organisation Humara Bachpan encourages kids to draw the changes they want to see in their neighbourhoods. The work makes underserved areas visible and gives meaning to density and shape to disconnection; magnifying needs often overlooked by adults. Maps are fed back to local councillors, who have the power to enact change. The value of child-led mapping isn’t only about pinpointing local pleasures and pains but more about activating these latent citizens.

In Karachi, Pakistan, the educator and artist-led initiative Bachon se Tabdili (Change Through Children) aims to re-envision public space by empowering its most marginalised, but active, agents. Working with 11 government schools to develop visual languages to enable the expression and sharing of children’s experiences of negotiating a dense urban space, Bachon se Tabdili has helped to make visible the plots, streets and rooftops that act as de facto play spaces in the absence of any dedicated by the city. Their mapmaking forces us to confront the plurality of a city, the “impossibility of totalising fixed representations” [9].

Children are essential social and urban agents – citizens, not future citizens. The imaginings of their future aren’t blurry. Suspend any aesthetic inhibitions, and you may divine their concerns, hopes, disparities, possibilities for their future world.

MAPLAB: INTENT

Inspired by this work, we at Superflux developed MapLab within the DATAstudio programme, working with Robbert Storm and Liselotte de Groot from local studio Beam it Up and later joined by Sophie Rijswijk, a student in urban planning at the Eindhoven University of Technology.

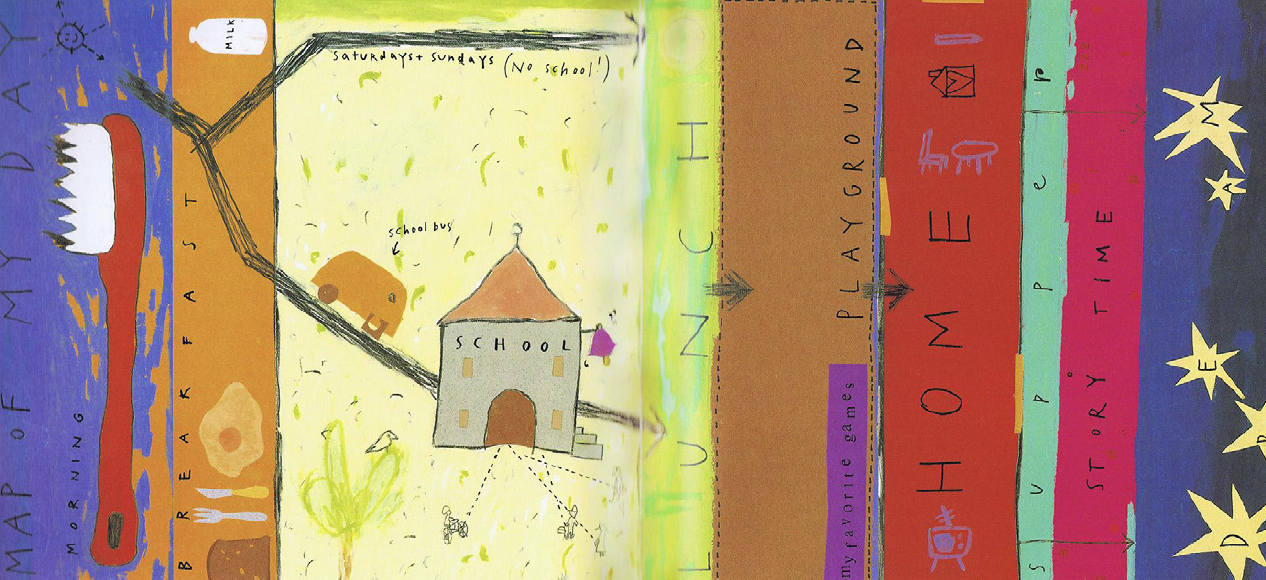

In her book You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination, Katherine Harmon shares a wide-ranging collection of superbly inventive maps, including the work of Italian artist and illustrator Sara Fanelli, who charts various facets of a child’s world and inspires kids to create their own maps.

We aimed to develop a programme of activities with schoolchildren in Eindhoven aged 7 to 12 that would engage them in deconstructing the map and bringing to the surface the thick layers of imagination and alternate uses for the spaces they spend so much time in. The intention of MapLab was twofold:

1. To bring to life that distinctively imaginative layer that is not about data sets but about stories – where a house can be a castle, a sidewalk the home of dragons; where lines between fantasy and reality blur. We were interested in giving form to the imaginative conceptual maps that bring meaning to the territory of social life.

2. To understand how to truly become open to seeing the city from the point of view of children, in order to revise, modify, edit and design cities that work for all. And, in doing so, to reflect the children’s individual and collective perceptions and hopes for the neighbourhood they call home.

PILOT: A CARTOGRAPHY OF IMAGINATION

We developed a pilot project to explore how we could collaborate with schoolchildren to generate new and alternate maps of their neighbourhood. We were thrilled when the elementary school De Tempel, located in the De Tempel neighbourhood in WoenselNoord, said it was happy for us to work with its pupils (aged 7 to 10) to roll it out in late 2016.

For the MapLab pilot, we conducted four workshops over the course of a month in the school with the children. In an iterative process, we developed the strategies and tools for each workshop based on the children’s feedback and responses.

We started off by reading a paper version of the local map with the children and inviting them to identify places they knew and were familiar with. We specifically chose to start with an existing map rather than creating one as the outcome of the workshop to make explicit the limitations of any such map.

Kites provide wind and sun energy to the city; small power stations sit on top of buildings. Photo: Superflux

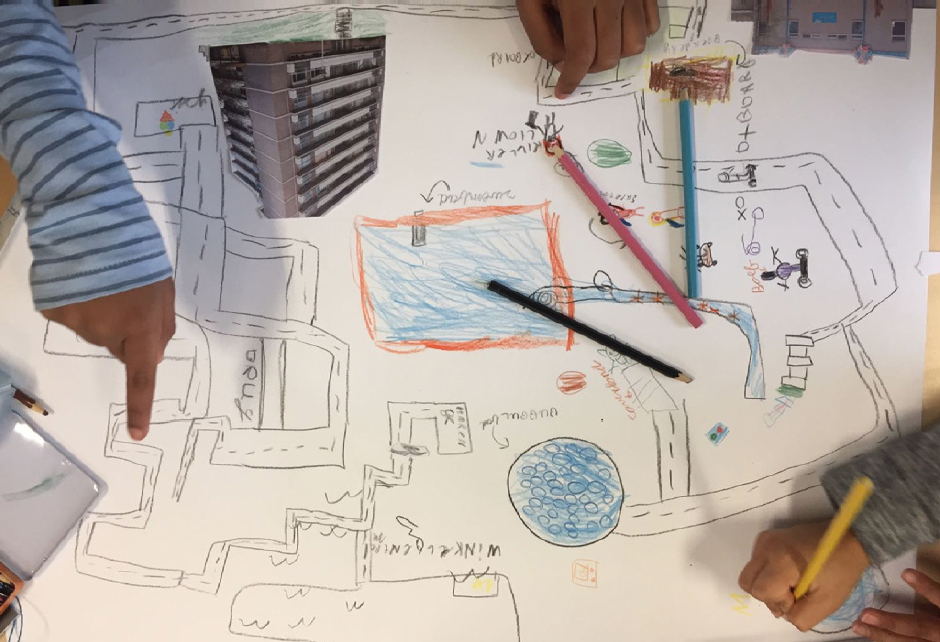

Additionally, we encouraged the children to annotate and colour-code areas and locations of significance: places they spent a lot of time in, ones they were scared to walk past, places that were haunted, areas which were “full of secrets”. Then we embarked on an intentional dérive [11] of sorts – intentional because our ambitions for the activity were made clear – but at the same time, we stayed open and exploratory towards the possibilities that might open up if we walked around a familiar territory with new questions. The children had diaries, pens and cameras as documentary tools, and their memories, shared rapport and intimacy as conceptual tools, for recording their discoveries, stories, fantasies and ideas.

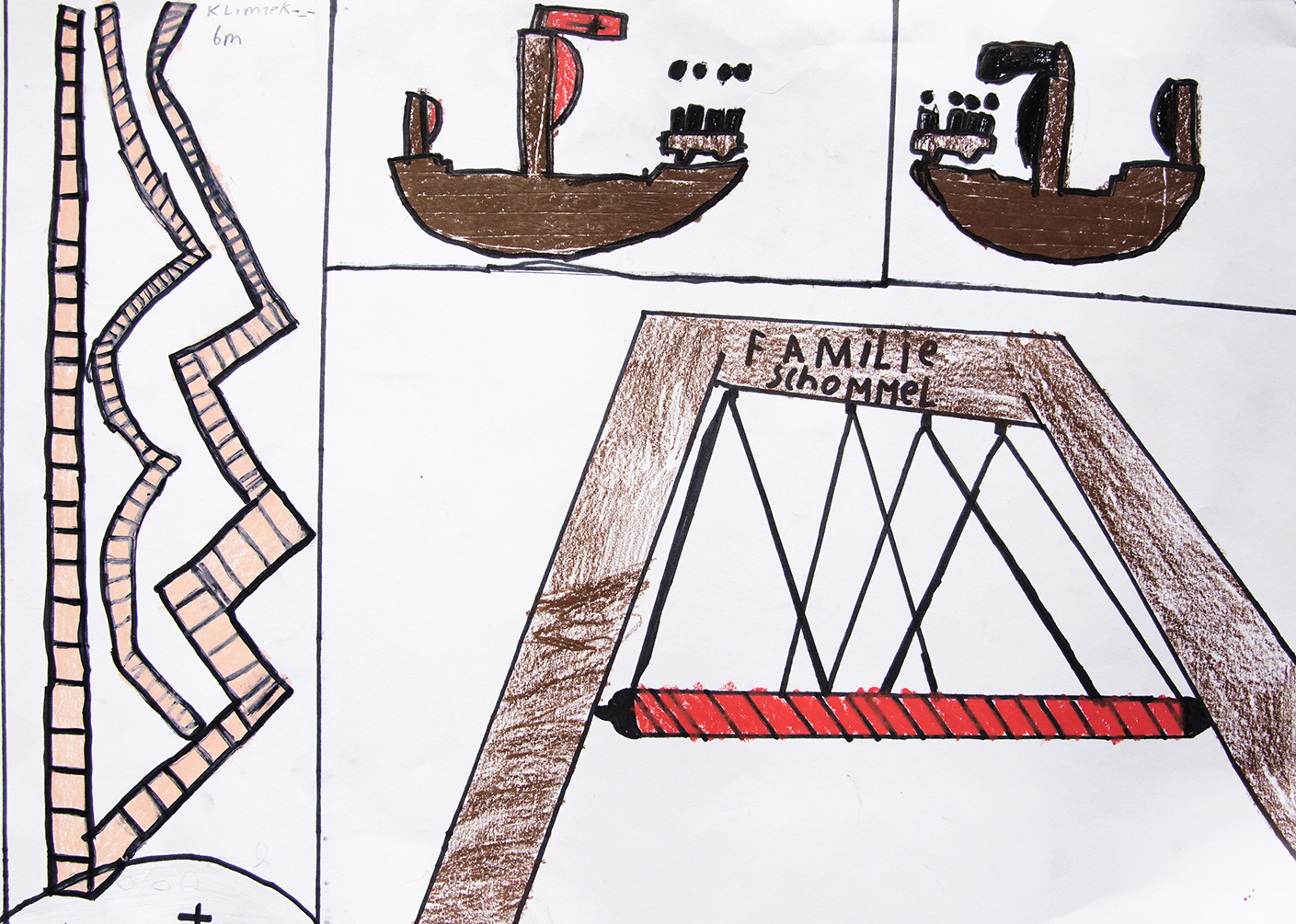

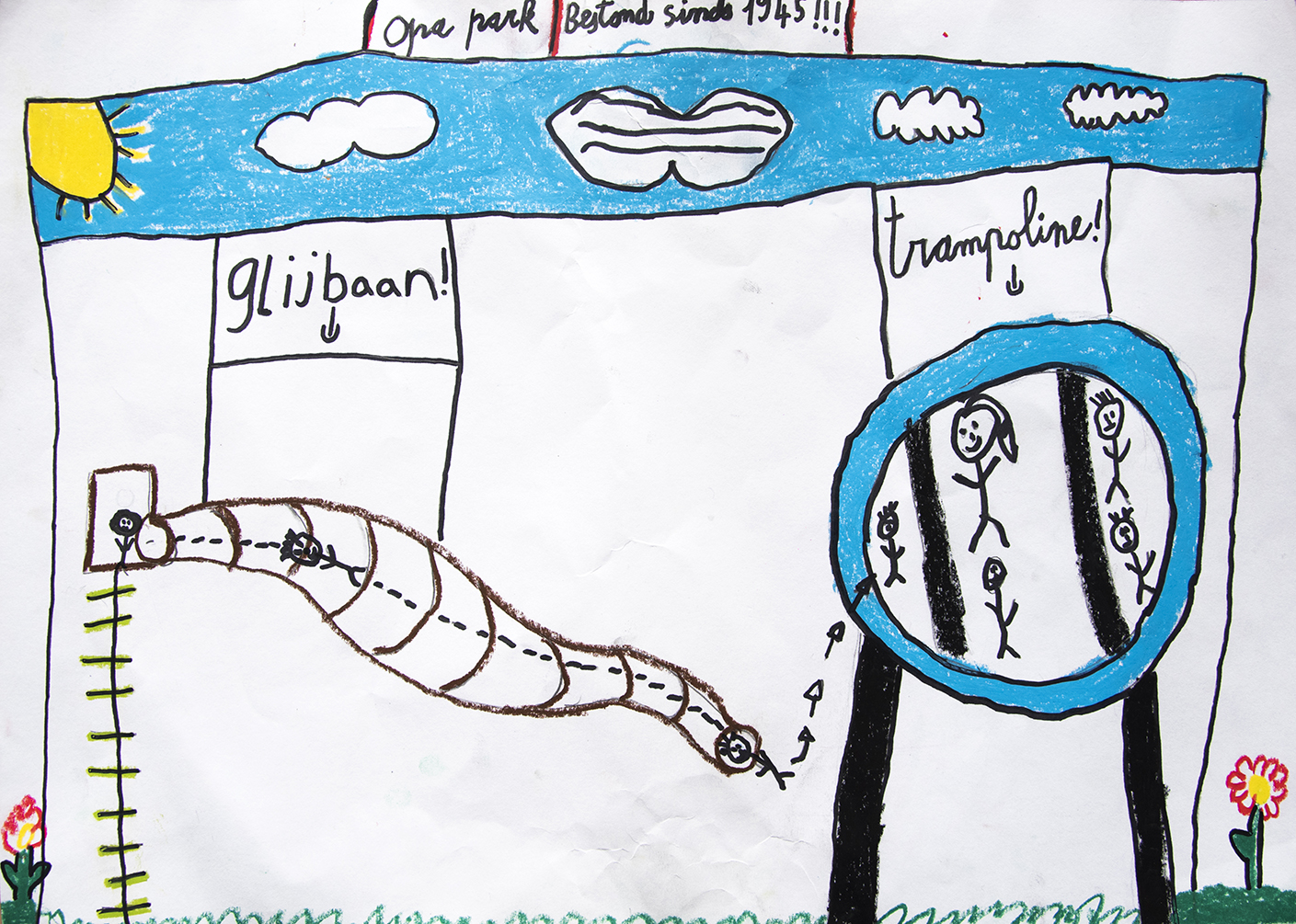

In the sessions that followed, we worked with the children to make drawings of their discoveries and begin to consider the futures of their neighbourhood and their spaces for play and social congregation. As they started working in smaller groups, they moved away from a locational planning map to generating “drawing maps” – layering locations and geographies with the fantastical but also the practical – combining technological utopias with social inclusivity and geographical freedom with environmental responsibility, and so on.

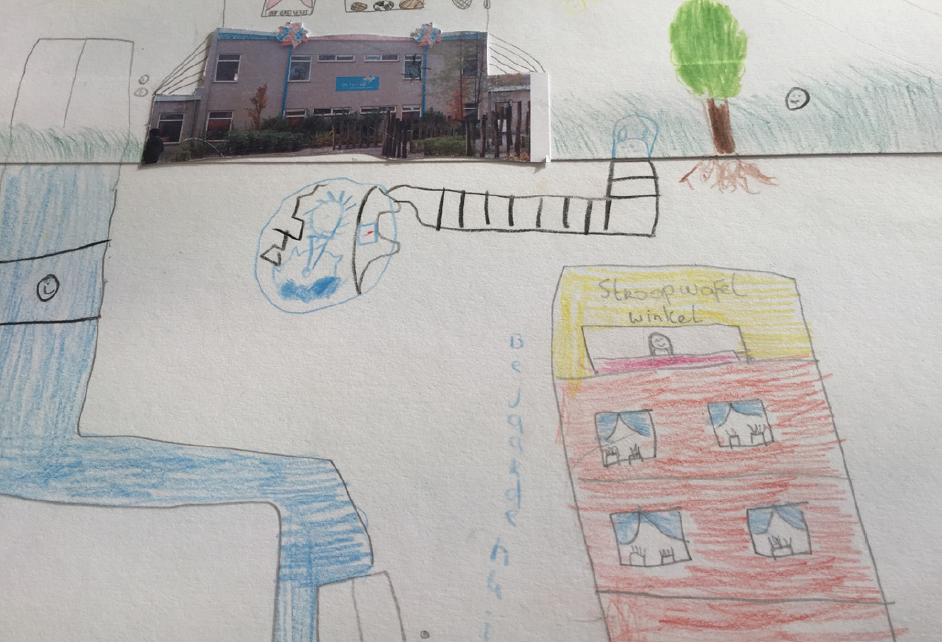

A shop selling the famous Dutch stroopwafels sits on top of a home for the elderly so shoppers can visit residents and share cookies. Photo: SuperfluxChildren from De Tempel primary school designed a zoo for a spot where there used to be a supermarket. Pedestrians can easily cross the motorway thanks to a new zebra crossing. Photo: Team MapLab

The children’s drawings also offer us a means of describing and understanding the intangible: everything from air routes and constellations to states of mind. And here I want to share snippets of their ideas, as illustrated by them: “urban wildlife sanctuaries”, “cookie shop on top of elderly homes so people shopping for waffles can visit old people and share a cookie”, “vertical farms”, “teleportation to the moon”, “dome over the school with easy weather control. Want snow? You got it”, “an underground archaeology museum”, “a hotel where the rumbling stomach of a turtle wakes you up in the morning”, “more tunnels, bridges and caves in the city”, “kites that provide wind and sun energy to the city, with small power stations on top of buildings”, “retirement homes for old robots running on fossil fuels”, “random houses in streets where people can just enter and play games together”, “collapse of the Netherlands and its merger with Morocco”, and finally “some ‘alone-time’ spaces when everything becomes overwhelming”.

It might be easy to judge and even dismiss these ideas and drawings from an adult perspective, but that’s not the point of the activity. If anything, it’s the opposite – it’s a matter of reframing and translating children’s ideas into an easily digestible format for adults, so that nothing remains hidden. Let us take a moment to see how the adult world is affecting young people; to reflect on their interpretation of this modern world we have created for them.

The pilot showed how the concept of the map is actually much broader and expansive than its current use suggests. Our intention was to work with tools used to navigate spaces today, then relocate the children into new perspectives, both spatially and imaginatively. The physicality involved in this act of cartography was equally important – getting the children outside and walking around, something they don’t do whilst in school. We wanted to continually oscillate between the imaginative and the practical, not so much drawing connections between locations but zooming inside a space, opening it up and giving that dot on the map some weight, depth and dimension.

The most significant success of the pilot was the children’s sustained engagement, stimulation and enthusiasm throughout the process. The project also met with much openness and appreciation by their teachers, and by a local social worker, who was visibly surprised by the depth, spirit and nuance of the kids’ ideas. This became an incentive for us to keep going.

Based on our experience with the pilot, we realised that MapLab had the potential to emerge as a field guide to the visions, ideas and voices of the children of Eindhoven. If we could present this to the local planners, developers and councillors as an additional layer to the existing map of Eindhoven, where would that take us? We wanted to find out. So we decided to further develop and scale the MapLab workshops to a few more schools.

SCALING MAPLAB

As we reflected on the pilot, it became apparent that we needed to narrow the scope of the activity and project area so children could explore the entire territory. We also needed to create a methodology and toolkit that would be easy to use and scale across different schools, develop a better way of documenting the stories as they emerged, and share all outcomes digitally. The educators were keen for the workshops to be grounded in the physically plausible, real and believable.

So Beam it Up designed maplabkids.nl, a brand new website tool and living archive that would become central to the workshops, alongside methods gleaned from the pilot. Between September and November 2017, Beam it Up and Sophie conducted MapLab workshops in four schools across Eindhoven.

Pupils from Louis Buelens primary school documented the mess in the park. Young people, in particular, leave behind a lot of rubbish and food. Photo: Fieke van Berkom

Each workshop kicked off with locating the school on the MapLab website in the classroom. Beam it Up introduced the digital map to the children, who then examined it collectively and circled their chosen research territory around their school up to 250 meters in diameter. After discussing the area in greater detail – secret spaces, haunted spaces, spaces where they felt comfortable and spaces where they didn’t – the children annotated their spaces on the map with four different colour codes. Each child had his or her unique memories of the space, and that tacit knowledge was brought into the discussion about how they felt about the space, where they felt uncomfortable, what they loved and so on. On the basis of the discussions, they took pictures at each spot, and the facilitators helped them upload the selected images to the MapLab website with hashtags and descriptions.

This screenshot from the app maplabkids.nl, zoomed in on Eindhoven, shows the locations the kids explored along with the photos they took there.

A screenshot from the app maplabkids.nl, zoomed in on the topic of the river De Drommel. A star on the map indicates the location the solution addresses.

A screenshot from the app maplabkids.nl, zoomed in on the “improvement” category (#Mlverbeteren). All photos relating to this tag are shown on the right-hand side of the screen.

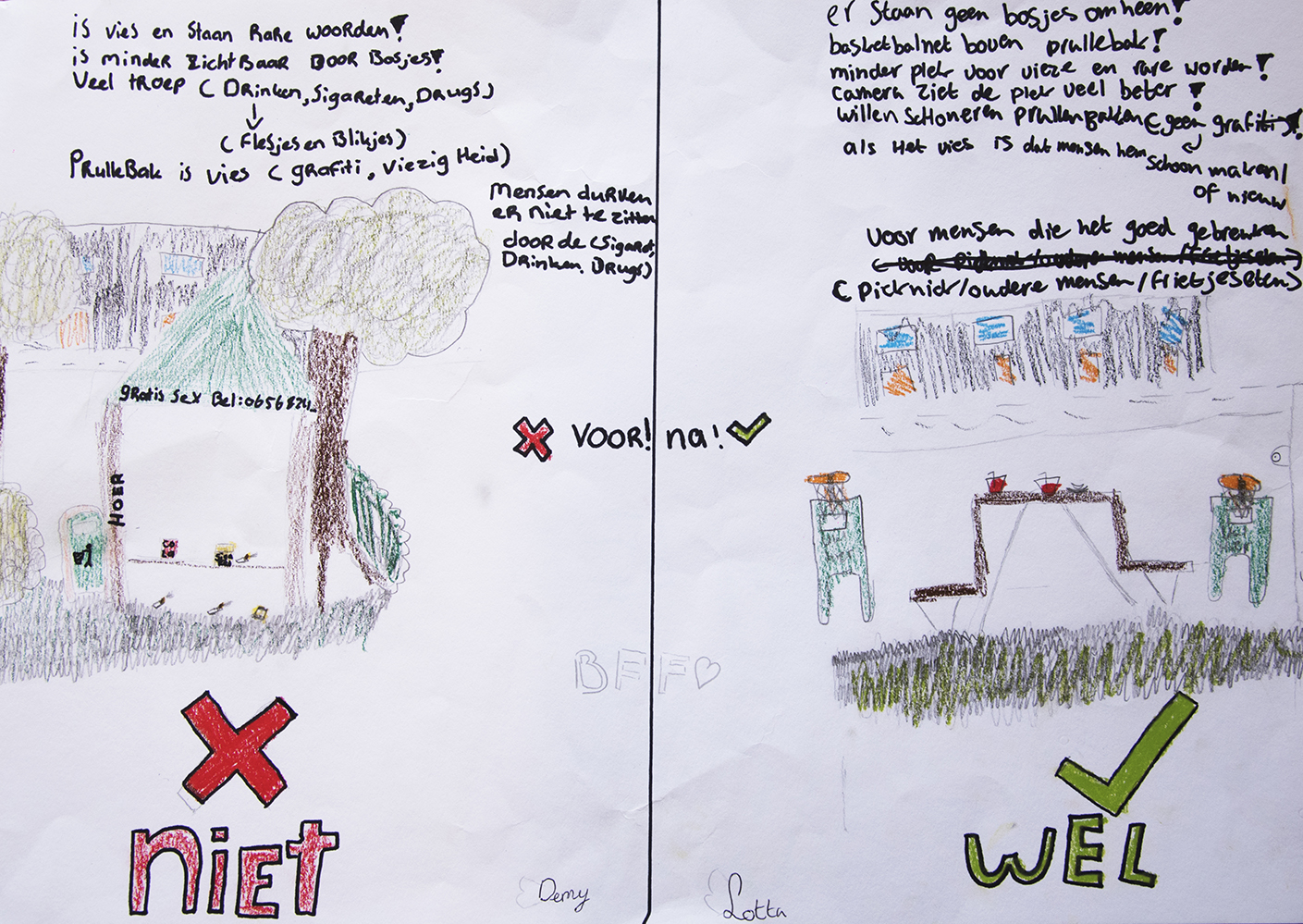

In the next workshop, the children gathered around the MapLab website to share observations from the previous session. Through guided discussion about the unpleasant spaces that had emerged in the first workshop, they got an opportunity to edit the map, removing or adding spaces marked for improvement. After the map was completed, the children went into the field again to analyse these spaces more carefully. What would they like to see different? What did they want to change, improve, alter, modify? Was it a spatial or a functional improvement they wanted or a behavioural change? Was it about feeling a sense of shared ownership to the space or a sense of mutual respect among all those who use public spaces?

Then the children worked in pairs to create alternate versions of the spaces they’d visited by writing short texts and making drawings. In the third and final workshop, the children finished their drawings and presented their ideas, which were added to the MapLab website in the form of a picture with a short description and hashtags.

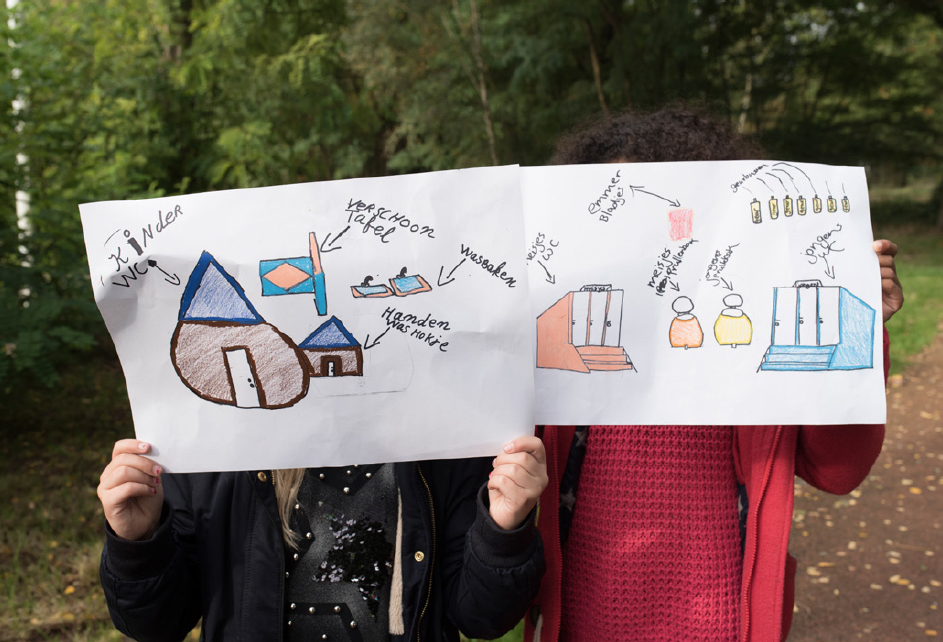

After noticing there were no convenient loos they could use while playing outside, two girls from Strijp Dorp primary school proposed building compost toilets for boys and girls. Photo: Fieke van Berkom

Kids from Strijp Dorp primary school show their design at the location it’s intended for. Photo: Fieke van Berkom

EXAMPLES OF IDEAS THAT EMERGED

DOG BIN WITH BENEFITS

While Kees Bolplantsoen is one of the few green spaces in the neighbourhood, the overwhelming amount of dog faeces there makes it unconducive to play. The duo behind this design – a dedicated bin that offers free poo bags and exchanges dog biscuits for poo – proposed behavioural nudges to encourage good behaviour.

ACCESSIBLE COMPOST TOILET The neighbourhood around Strijp Dorp school, like many across the globe, has a sanitary issue: the absence of safe toilet facilities for girls. While biology allows boys to urinate in bushes with little disruption to play, it’s harder for girls. This solution considered equal access for all genders, other human factors, and the environmental impact of human waste. The girls designed a compost toilet whose base is composed of green waste. When it’s full, the compost is given to farmers.

DE DROMMEL The duo behind this design – a personal favourite of mine – concentrated on developing a construction system that would conserve the water stream, including its delicate ecosystem. To accommodate fish traffic negotiating a construction site, they devised a system of nets to filter shoals from litter and ferry them away from it. If a scanner detects life within a ferry net, the fish and other creatures are safely deposited back into the stream; if the object is litter, it is filtered into a trash can. This project is aptly named de Drommel (de Dommel: the river; rommel: trash).

PLAYGROUND Tackling boredom was the driving factor behind this design. Inadequate drainage has made a soccer pitch useless, driving children indoors and into the company of video games – a temporary solution (they recognise that this too will soon become boring). More importantly, discussions identified the link between boredom and anti-social behaviour – older youths terrorising younger children and vandalising the playground. A duo from De Driesprong school designed a system that addressed the need for a sense of security and sustained engagement to combat the affliction of a fear of young people: cameras are installed in conjunction with designated areas where graffiti and the demolishing of “stuff” are encouraged.

WHERE CAN MAPLAB GO FROM HERE?

It has become evident through our work with MapLab that children are highly enthusiastic and energised about the activities. The participants presented their ideas at Dutch Design Week to the mayor, a city officer tasked with overseeing Woensel, and a social designer. The mayor was clearly moved and surprised by their presentations, specifically proposals that creatively employed wit to inspire behavioural change, and suggested that perhaps the city government should institute a young people’s panel so their voices and perspectives could be heard. This was heartening to hear, and the DATAstudio will follow up with local councillors to see how MapLab can be further implemented.

We are keen to see if the MapLab methodology and tools can become part of schools’ curricula across the city. There are a few popular school subjects in the Netherlands into which MapLab fits in very well. One is research and design learning (“OOL” in Dutch), in which students conduct research from their own research questions or design solutions for problems or needs they have identified. It is an educational learning strategy that draws on 21st-century learning skills. The project also fits into the mandatory subject of citizenship education. An important aspect of this is that students learn about their own living environment by contributing to and taking responsibility for it. Plugging our programme into these activities could become one way of extending education outwards into the community and the city, enabling kids to develop a sense of shared civic responsibility and ownership from a young age.

Two girls from Strijp Dorp primary school worked on an idea for reducing the number of stinging nettles on a playground. They proposed building better and more attractive footpaths. Photo: Fieke van Berkom

EMERGING INSIGHTS

As Het Nieuwe Instituut plan’s the next phase of MapLab, this record serves as a useful means of reflection on the activity, and here I want to share some of our emerging insights.

1. Children were excited about coming up with ideas and “solutions” to what they considered “problems” in their neighbourhood. Younger children felt that their sense of ownership of the playground was compromised by the presence of older youths, while older youths felt excluded and without a sense of place. This is a complex social challenge, and the absence of safe, shared spaces is a problem in many cities.

2. Whilst the children endeavoured to find meaningful solutions, the challenge of solving the real underlying problems remained. What quickly emerged was an understanding that complex issues aren’t accompanied by easy answers and that the solution to one problem often births another problem. What are the implications of planting consequential thinking into education?

3. In this project, critical thinking amplified children’s awareness of their neighbourhoods, and they learned to look at their direct environment topographically, working with a map to navigate their neighbourhood, understanding that a map is not synonymous with territory. This practice also demonstrated how the digital tools used to navigate and photograph are precisely the same tools that can be used to alter the story – to make visible the plurality and messiness underneath the flat overviews that are used to make decisions.

Kids from Strijp Dorp primary school designed improvements to a BMX track. It hangs in the air, creating a steep drop. The kids proposed placing a fence around it. Their colourful solution brightens up the track and makes it safer. Photo: Fieke van Berkom

4. Connecting the dots from issues to problematic behaviours to spaces to facilities was often overwhelming. Though the kids didn’t manage to solve all their neighbourhood problems, they were challenged to find different paths towards a solution. They were activated as social agents.

5. Along with being independently activated, the children discovered the challenges of collaborative work: the need for attention and dialogue; the perils of attachment to one’s own ideas and the importance of recognising different perspectives; the need to understand when to work together and when to work alone. These discoveries were both critical and unnerving and allowed them, in an abstract way, to acknowledge that plurality is vital to communities.

CONCLUSION

The MapLab experiment is neither new nor unique in this genre of practice. But for the children and collaborators who were involved, it was new and exciting. DATAstudio hopes to continue developing this work and essentially to create a vast archive of thick data generated from the perspective of the children of Eindhoven. We hope this data will be viewed as a rich source of inspiration for the design, planning and creation of more participatory, inclusive, accessible, playful cities.

As we have learnt, for children, the local neighbourhood is often the only space where there is a sense of familiarity; it is a space which shapes their worldview and one where civic learning begins. What to us appears as a small geographical area can to a child be a continent of imagination, rich with stories and fantasies interwoven into seemingly mundane things and places. We hope experiments like MapLab can give life to the rich stories, imaginations and creative aspirations of a group of citizens who typically are not involved in shaping our cities.

I would like to thank the DATAstudio for inviting me, and comrades Jon C Flint, Jon Ardern and Nicola Ferrao from Superflux for their collaborative efforts on this project.

REFERENCES

[1] Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961).

[2] See: https://eindhoven. buurtmonitor.nl, retrieved on 30 January 2018. 41

[3] Alfred Korzybski, Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics (Lancaster: Penn., 1941).

[4] Lindsay Caplan, “Method without Methodology: Data and the Digital Humanities”, e-flux journal (2016).

[5] Tricia Wang, “Big Data Needs Thick Data”, Ethnography Matters (2013). Michael Jensen, Untitled (Revenge Map), 2003.

[6] Greg Halseth and Joanne Doddridge, “Children’s cognitive mapping: A potential tool for neighbourhood planning”, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, vol. 27, 565–582.

[7] Sam Sturgis, “Kids in India Are Sparking Urban Planning Changes By Mapping Slums”, City Lab.

[8] Katherine Harmon, You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2003).

[9] Shahana Rajani, “Urban Narratives of Children’, Cities Plus (2014).

[10] “In pictures: Kids in space – children draw their visions of the future for Nasa”, The Telegraph (2017). Rashiq Fataar, “Children draw their visions for Future Cities”, Future Cape Town (2012).

11] Guy Debord, “Théorie de la dérive”, Internationale Situationniste #1 (Paris, June 1958); translated and published by Ken Knabb as “Theory of the Dérive” in Situationist International Anthology (Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets, 1981 and 1989).