Projects

MANGALA FOR ALL

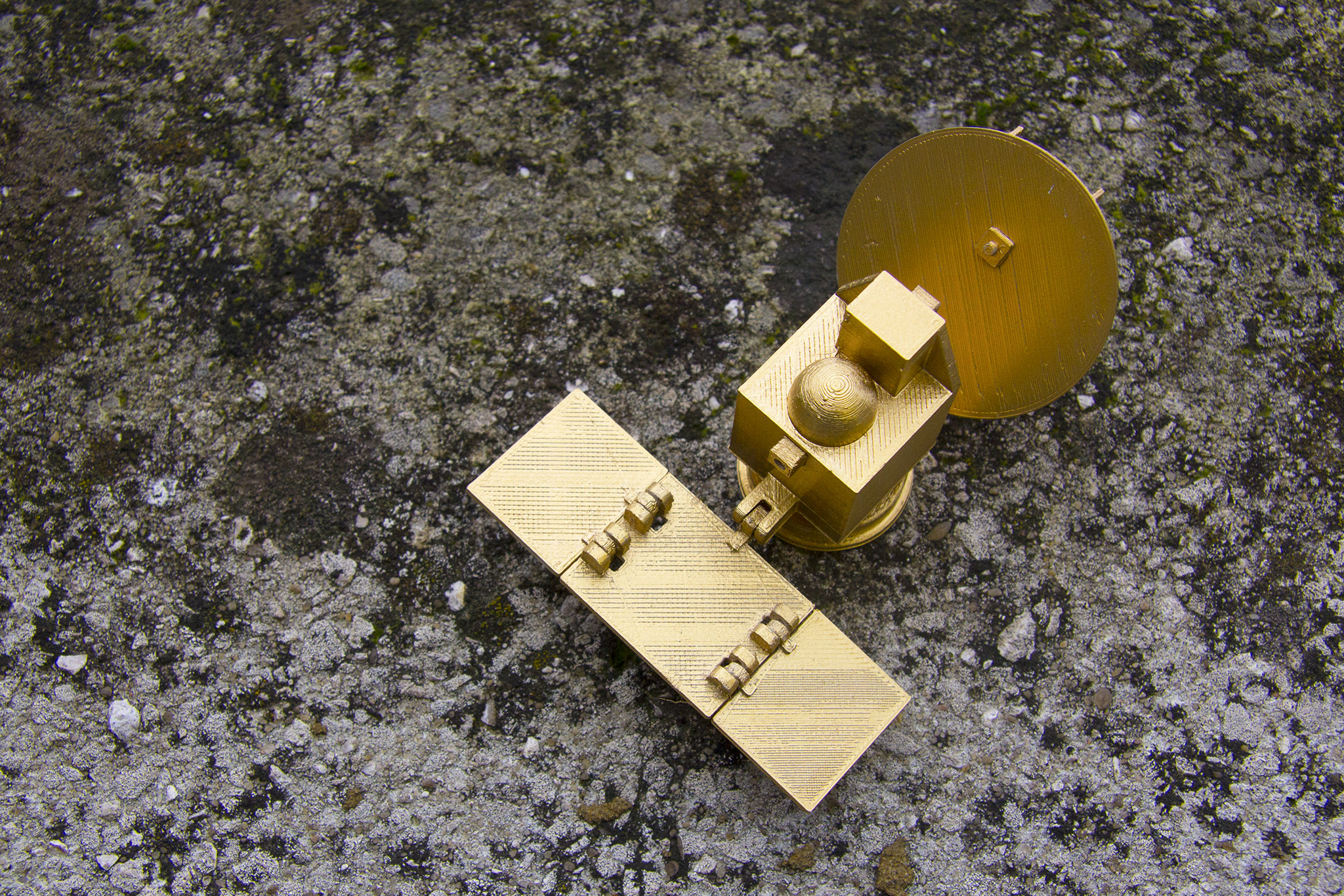

Mangalyaan, or the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) is an Indian spacecraft orbiting Mars since 24 September 2014. To coincide with this mission, Superflux Lab launched ‘MANGALA FOR ALL’, a reflexive ethnographic performance. Working with the aesthetic of the Indian street, where cheaply made plastic trinkets often attain god-like status, we made over 50 miniature, deified versions of the Mars probe in our studio. We then roamed the streets of Ahmedabad, India, with these Mangalyaan Miniatures, which we offered in exchange for insights into what Mangalyaan means to those we meet.

Recordings from over 40 interviews have revealed a more tenuous relationships between citizens and such state-funded Space Programmes. The interviews are full of poignant and surprisingly playful stories of jugaad, scientific innovation, resourcefulness and creativity, alongside the hidden narratives of nationhood, geopolitics and the space race.

We are now in conversations with ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation), PRL (Physical Research Laboratory) and Vikram A Sarabhai Community Science Centre to find the best means of translating and incorporating the project’s emotive insights into community education programmes.

Our design process are being document on a tumblr which we recommend visiting. A film is also currently being edited and we hope to share it soon.

PROJECT CONTEXT

by Anab Jain

I grew up in Ahmedabad, in the shadow of the Community Science Centre, a space for science exploration founded by Vikram Sarabhai, fondly called the “Father of the Indian Space Programme”. My friends and I often spent hoursthere, playing with the colourful wooden models, learning about Newton’s Laws, and helping out with what seemed like important Chemistry experiments. The short walk between the Science Centre and the Quarters, where we lived, was however populated with Bhoot (supernatural creatures or restless ghosts of deceased persons). Or at least that is what we were made to believe from the highly detailed historical accounts of the doodhwallah (milkman), fruitwallah(fruit vendor) and chaiwallah (tea seller). Ghosts with unfulfilled dreams who wandered idly in the dark, overgrown fields on either side of the quiet road that took us home. Ghosts who had encounters with Vimanas, ghosts who lived in parallel worlds, ghosts who moved seamlessly between alien planets. There were never enough ghosts, or Amar Chitra Kathas for us to devour.

Whilst our imaginary landscapes were populated with mythological fantasy, science lurked in our backyards and school corridors. A visit to the nearby snake park would invariably involve crouching on our stomachs to peek into the highly secretive compound of ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation), and catch a glimpse of the enormous, gleaming rocket that stood at its entrance. That rocket and its ancient, mythological ancestor, the Vimana, are forever etched in my memory. Back home, we would huddle around the Quarters’ only black and white television to watch a Bollywood songs program on Doordarshan, powered by INSAT 1-B. As the television alternately beamed its noise and signal, the message “This is an INSAT 1-B Transmission” was distinct and clear. We were always in direct communication with our satellites.

Growing up in this continuous-split-world of science and mythology has shaped my worldview in more profound ways then I would then have realised. It also gives a glimpse of how there is almost no dichotomy between science and mythology in the lived reality of the Indian population. The ambitions for progress for a young independent nation were acutely interwoven with its 5500 year history. The aspirations of the Indian Space program reflects this relationship, and was eloquently described by Joanna Griffin as a ‘uniquely poetic alliance between high-end technology and grass roots needs’.

A VERY BRIEF HISTORY

The foundations of India’s Space Programme were originally laid by Homi J. Bhabha, a nuclear scientist, founder of Atomic Energy Commission and instrumental in shaping India’s ambitious nuclear programme. Vikram Sarabhai succeeded Bhabha, and worked with Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister to set up Indian National Committee for Space Research INCOSPAR– which then became ISRO.

India made clear that ISRO’s plans for space technology were driven by “real needs” on land, which became apparent through the INSAT, SITE and several other programs in the decades to follow. The INSAT satellites broadcast television to remote villages, providing education and information on farming and healthcare.

Whilst NASA’s historic records suggest that the rise of ISRO, and the INSAT programme was a distinct case study in the emergence of a nation-state in South Asia, there is also a contrary belief that the nation’s Space Programme reflected a quality of humility lacking in the competitive ‘Space Race’ drama being enacted between USSR and USA. And that is perhaps because, “a powerful tie of space technology to the transformational potential of science through nation building has been forcefully present in the collective imagination of Chandrayaan (and indeed all other space launches) within India”, according to Griffin. ISRO has gone onto becoming one of the world’s largest government space agencies, and a formidable member of the international space race with its Chandrayaan-1 mission to the moon, now Mangalyaan to Mars, and Aditya to study the Sun in a couple of years.

WHY ‘MANGALA FOR ALL’, WHY NOW

So when, couple of months ago, Mangalyaan was launched, questions around the launch surfaced yet again. Was it yet another act of nation building, or was it a symbol of progress and development? Was it the Indian elite’s delusional quest for superpower status as economist-activist Jean Dreze commented? Or a way “to dislodge the perception of India as a developing nation, by showcasing spectacular technology”?

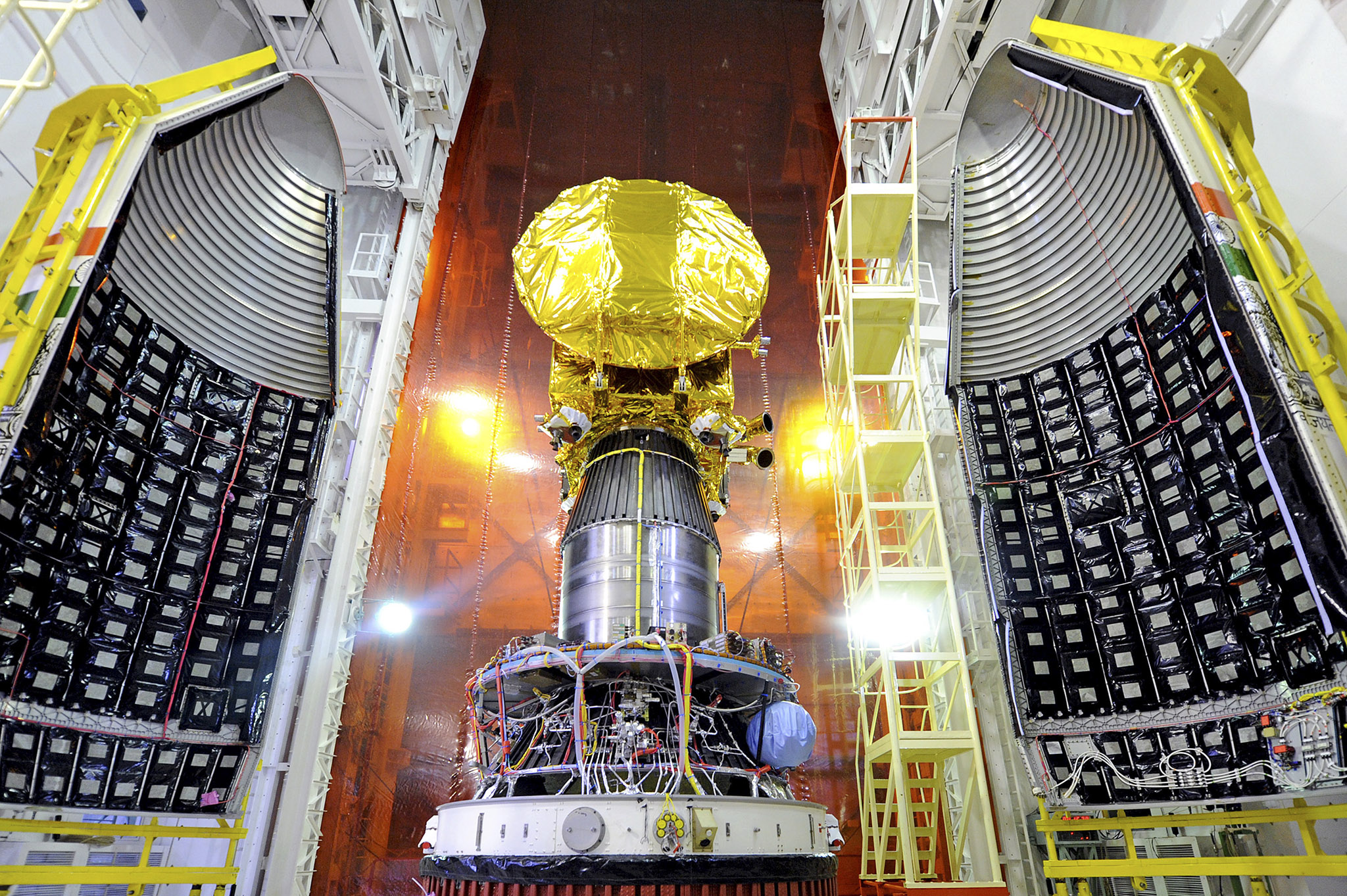

It was a certainly a proud moment for ISRO, as India became the first country in the world to insert a spacecraft into the Martian orbit in its very first attempt, and ISRO the fourth space agency to reach Mars after Roscosmos, NASA and ESA. The mission was completed in just 14 months and $75 million with little prior expertise, and proved to be one of the cheapest in the world, the country’s most audacious and successful example of jugaad so far, according to the Guardian. The national press went berserk, as the Prime Minister hailed it a testament of India’s talent. So did the international press, though not quite in the same way. The New York Times published this cartoon, for which they later apologised. The Economist came up with a rather tragic headline. But soon our newsfeeds were flooded with this picture, showing ISRO’s female scientists celebrating. It broke all stereotypes, nationally and internationally.

At Superflux Lab, we felt the time was right to explore and understand the multidimensional side of any such scientific endeavour and explore the themes that such a space programme presents. Stories of jugaad, scientific innovation, resourcefulness and creativity in Mangalyaan’s success were entangled with assumptions about its impact on people’s hopes and aspirations, as well as the hidden narratives of nationhood, geopolitics and the space race.

This is the reason for MANGALA FOR ALL. At Superflux, we have designed and manufactured 50 Mnagalyaan Miniatures, a deified version of the Mars Probe, as an artifact for investigating the questions around power, science, progress, development and jugaad-innovation. We have worked with the local, cultural aesthetic of the Indian street, where cheaply made plastic trinkets often attain god-like status, as they become objects of adornment and worship. What place might a space probe have in your autorickshaw, bicyle, car or kitchen?