Blog

Experiments in Indoor Farming

From Aeroponics to Fogponics, Kratky to Permaculture, we present a glimpse of our indoor farming experiments, methods and prototypes developed for ‘Mitigation of Shock’.

Five years ago, we began Mitigation of Shock by imaging one possible future in which supermarket shelves lie empty. We imagined the confluence of elements leading to this future: economic instabilities; broken supply chains; simultaneous crop losses in the world’s major breadbaskets.

Mitigation of Shock tries to understand what it might mean for people to adapt their domestic lives to thrive in such a future: everyday people resourcefully fixing and making their own tools; growing their own food; sharing skills and offering mutual support and care to those that need it in their local communities.

Until very recently, this future may have felt very distant, dystopian almost, to most people. COVID-19 has now pushed this possible future right into the foreground.

Mitigation of Shock, first shown at Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (October 2017 to May 2018) and more recently at ArtScience Museum, Singapore (November 2019 to July 2020), is an immersive installation that makes tangible the potential lived implications of the climate crisis. Visitors are able to step inside a local family’s home and directly experience what such a future might feel like: a living space shared with experimental hydroponic and organic food computers; a future brimming with examples of how we might have to adapt our way of living.

EXPERIMENTS IN GROWING FOOD INDOORS

Conceiving and producing both installations took months and involved many moving parts. Of course, there was some speculation, but our work for Mitigation of Shock was rooted in hands-on experimentation. For months, led by Jon Ardern, we surrendered half the communal space in our studio for trialling and playing with experimental growing systems, trying to find the most fruitful techniques.

In this post, we wanted to share some insights specifically into the food growing methods that we explored and adapted, the lessons we learned and how our approach changed because of them. We start with a few technical and equipment-heavy hydroponics systems and then explain our progression to a slower, permaculture-based growing approach. This isn’t meant to be a full step-by-step guide, but more of an overview of our process. In sharing these methods and tools, we hope that they might inspire your own experiments, or at least start some conversations!

PRODUCTIVE (AND PRECARIOUS) HYDROPONICS SYSTEMS

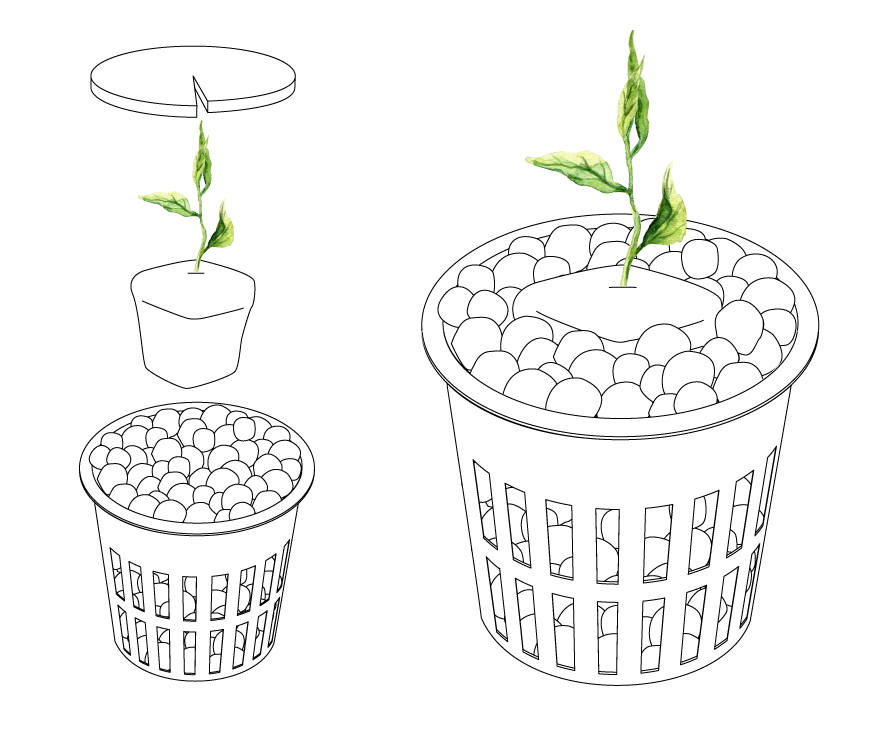

For most hydroponics systems, seedlings are grown in damp “rockwool”. We found we had more success if they were first germinated in a damp paper towel sealed in a plastic bag. Once their roots emerged, we placed the seedlings in the rockwool cubes. We then nestled each cube amongst a cluster of clay beads in a mesh pot as drawn opposite.

KRATKY SYSTEM

We began by setting up a straightforward “beginner” hydroponics system known as a Kratky System.

In a Kratky System, once the roots begin to grow out of the rockwool, the seedling assembly is placed in a pH balanced nutrient solution with the mesh pot immersed in the water. Plant roots require a constant supply of water, nutrients and – surprisingly – oxygen. The principle of a Kratky System is that the water is used up at the same rate as the roots grow. This means that a given proportion of the roots is always exposed to air.

Kratky is a simple system that we found works best with non-flowering plants. Give this one a shot for lettuce and kale!

KRATKY VARIATIONS

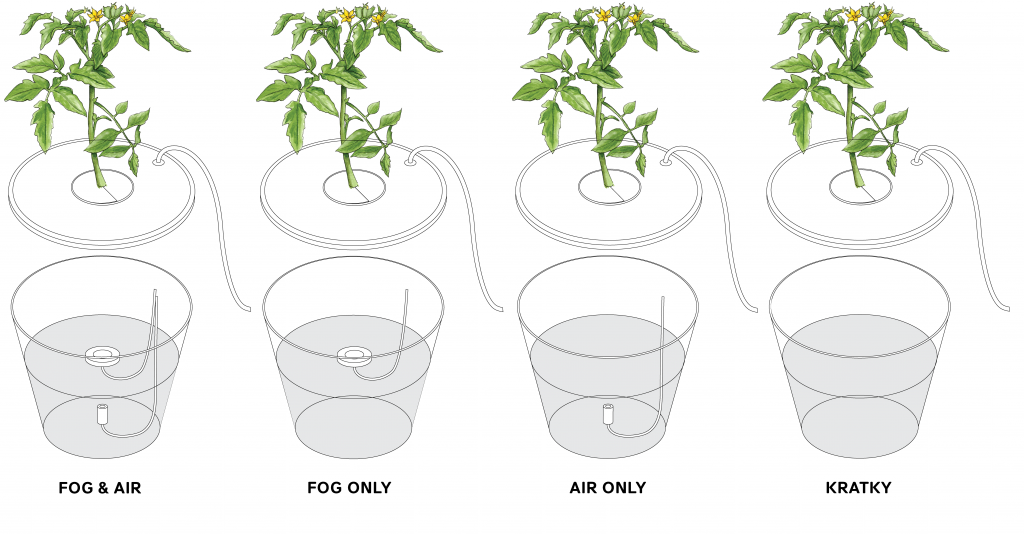

We also conducted a series of experiments building on the simple Kratky System, adding in a floating nutrient fogger to the surface of the water and air stones to introduce more oxygen into the system. The airstones appeared to have a minimal effect whereas the fog system definitely helped to accelerate growth, albeit with a little added complexity.

LOW-PRESSURE AEROPONIC SYSTEM

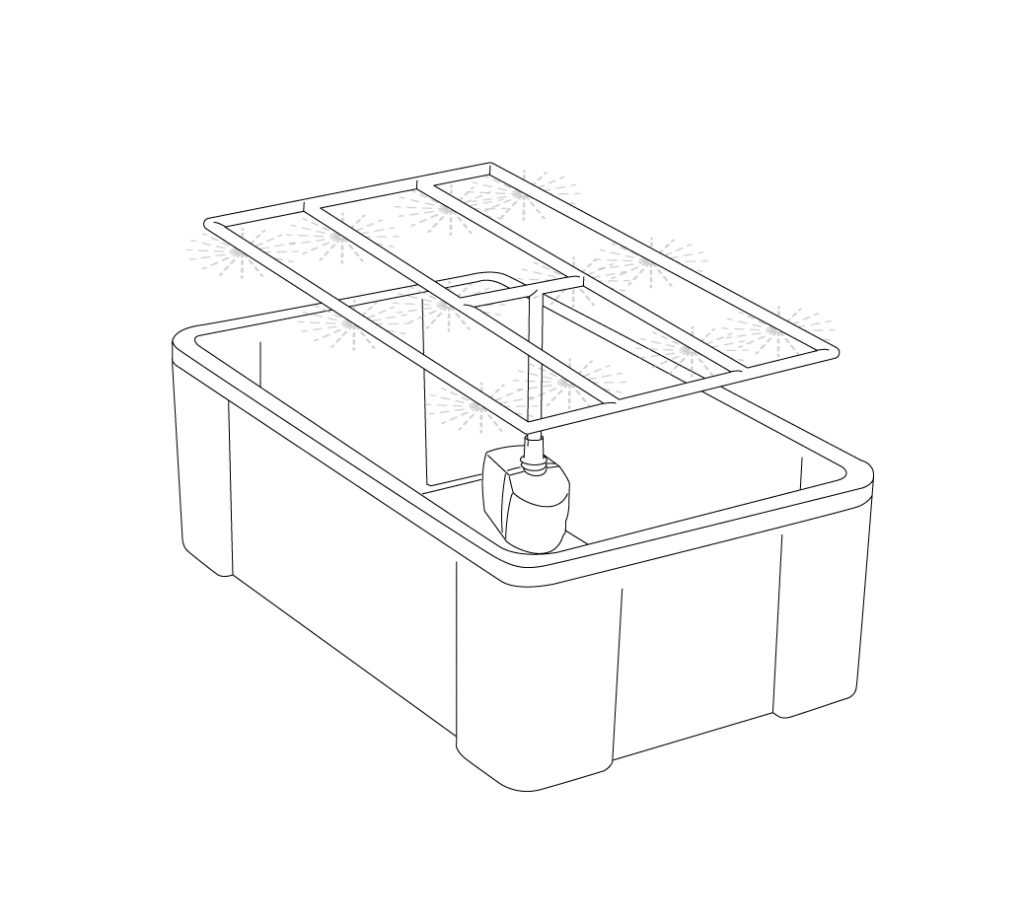

At the same time, we set up a more complicated Low-Pressure Aeroponics System in which plant roots are intermittently sprayed with water and nutrient solution by a pump system created using plumbing pipe and screw-in spray nozzles. In creating this system, it’s worth noting that we found we required quite a powerful pump and particular nozzles to get the spray effect we were looking for.

The Low-Pressure Aeroponics System was our most successful hydroponic system. We believe this might be because, after a few weeks, the roots of the plant would grow into the water reserve in the bottom of the tank creating a form of “hybrid Kratky”. The result was a “best of both worlds” scenario in which the system was productive but also resilient to failures in the relay system providing power to the pump.

SUCCESSES, FAILURES, AND LEARNING LESSONS

In the first half of summer, we grew plenty of chillies (later turned into chilli jam and spiced rum), an abundance of lettuce and kale, a good few tomatoes and a very large bean plant.

Around the beginning of the July heatwave, we started to notice our plants suffer. One day we measured the water in the Kratky Systems at 31°C, and they looked visibly unhappy. From this point on, the plants never fully recovered. We don’t know if it was heat damage or incorrect nutrient/pH balance as the plants’ requirements changed with maturation and fruiting.

Though this was frustrating for us, we were very aware that, for a family dependent on these food growing systems, a problem like this could have major consequences. All of our growing systems depended on stable and clean water supply (quite a lot of it!) and constant electricity supply. One failure or leak in the system and the plants would immediately begin to show signs of stress. If this wasn’t resolved within a day, the plant would be beyond recovery and our family could be left without vital food.

MATERIALS

System resilience wasn’t the only issue: hydroponic systems require a reliable supply of equipment and materials that also can’t be depended upon in a post-climate-change world. We built our grow systems from repurposed IKEA shelves; old piping and pond pumps; amended plastic buckets and salvaged Arduinos – we wanted to explore what might happen in a world where the current abundance of resources from our consumerist lifestyles begins to run out. What would we do, however, if even these materials and resources can no longer be found?

SHIFTING GEAR TO A MORE RESILIENT APPROACH

We knew it was vital to find more stable and sustainable indoor growing systems that could be relied upon in uncertain times. For this, we decided to turn to the permaculture movement for some ideas. In altering our approach, we also hoped to develop systems that would allow us to adapt what might be available naturally around us without causing stress to the environment. We wanted to explore what would change as skills and ecological experience increased, but the amount of reusable waste, devices and materials from the old consumerist paradigm decrease.

With a change in material approach, might the plants we were growing also benefit?

“We wanted to move away from a kind of scientific imperialism towards an understanding that nature is subtle and complex and that just because we only understand a system to need specific inputs doesn’t mean that it hasn’t adapted to maximally work with all the inputs of a given ecology.”

Jon Ardern

ORGANIC GROWING METHOD

Inspired by the principles of Organic Farming, Terra Preta and the No-Dig gardening movement, we created two “Organic Soil Beds” using mixtures of compost, biochar, vermicompost and a good dose of “live soil” found in the local park. We topped everything off with a living mulch of clover and “Strulch” (straw mulch) to avoid excess water evaporation.

Into these pots, we planted a carefully chosen mix of “Companion Plants” – plants that complement each other to create a balanced and more productive system.

Our aim was to turn the pots into miniature ecosystems: nitrogen-fixing plants provide nutrients for the soil; ground cover plants prevent moisture from evaporating; climbing plants use the taller plants to get closer to the light sources; worms circulate nutrients throughout the soil and, most importantly, invisible mycorrhizal fungi create and transport nutrients between plants.

LIGHT QUALITY

Where we’d been using grow lights that combined blue and red light to minimise energy consumption to yield output, we decided to switch to full spectrum warm white lights which closely mimic the sun’s full spectrum. Although on paper, red and blue light should be more effective, warm light provides for more of the metabolic activities plants require, allowing them to thrive in a slower, richer and more resilient way.

“The lighting systems are now moving towards lamps that more closely replicate the suns full spectrum rather than just red and blue that are more effective on paper but less in tune with the holistic needs of the plants.”

Jon Ardern

Soon our garden was overflowing with leaves.

A CHANGE OF ATTITUDE

It was around this point that we noticed an interesting shift in our relationship with the growing area at the back of our studio. Instead of eating lunch in our break room, we’d commune near the plants, enjoying the warmth of the light and abundant greenery contrasting the British weather.

We began to feel that growing in such a way might create a change in our social order towards an understanding of the subtleties and complexities of nature. We found a new respect for the beauty of natural systems and an appreciation of how we can work together with them rather than controlling them top-down.

We imagined the family living in our future apartment might move away from the resource-heavy food computers to a slower, more skill-based system. Perhaps they’d find paths to return to a non-anthropocentric way of life that simultaneously recognises the bigger picture.

If you can make it out to see Mitigation of Shock, Singapore at the ArtScience Museum you’ll see this change of attitude reflected in the installation. In Mitigation of Shock, 2050 (Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona), the actual living space of the family was squashed into the small kitchen area, with the living room primarily devoted to plant experiments. In Mitigation of Shock, Singapore set a few more years in the future, the family have rejoined the growing space.

The dining area is straddled by two bamboo grow structures over which creeping plants can grow. The family is not dining next to the plants but amongst them. Kids’ toys are scattered amongst the plants; whittling and woodworking tools rest against the pots showing that this area is used for slow and meditative craft done for enjoyment over necessity.

The apartment’s inhabitants have embraced this change to their home and way of life. Choosing to live amongst their new means of surviving, for reasons much deeper than self-sufficiency.

“The world has irrevocably changed and the family home is now a space to not only live, but to survive. The home is alive with multi-species inhabitants (insects and plants), surviving and thriving together in an indoor microcosm.”

Anab Jain

TODAY

COVID-19 has surfaced many challenges, and the growing panic and uncertainty around food supply chains is certainly one, we can begin to act on. In cities, it is unlikely we will ever produce all the food we need to thrive in our own domestic spaces, but learning, testing and experimenting will give us an opportunity to form new relationship with our food and hopefully change our consumption patterns.

We hope that some of our learning from building the Mitigation of Shock installation can help with such a transition. With imagination and resourcefulness, we can explore new possibilities around altered realities and ways of living.

FURTHER READING

- – One Straw Revolution is a must-read for anyone interested in natural growing methods (with a fair bit of philosophy thrown in).

- – The New Alchemy Institute has done some fascinating work around ecological systems and ways of living.

- – Of course, Kew Gardens is an invaluable resource to learn about plants and growing methods. We particularly enjoy visiting their student plots in the spring.

- – We couldn’t miss our favourite hydroponics practitioner. There is an amazing community of hydroponic, no-dig and indoor growers on Youtube. You don’t have to search for long to find tutorials for classic or innovative and experimental processes.